Lutana

The riverside locality of Lutana is a large residential suburb located between the Brooker Highway and the River Derwent. It was originally built by the Electrolytic Zinc company (EZ, the then operator of the Zinc works) as homes for its employees at the nearby zinc works. The refinery was built in 1916. The homes, in and around Cox, Furneaux and O'Grady Avenues, Cook Street and Bowen Road, were later sold off and are now privately owned. Lutana is the aboriginal word for moon. Other names originally proposed for the village included `Zincville' and `Gepptown'.

This village created for the Zinc workers is not to be confused with Drip Village, built at the southern end of Lutana on New Town Bay around 1950. This collection of concrete stucco finished homes were built to house the managers of the Zinc works. The village occupied Lallaby Road, Risdon Road and Turanna Street. Many of the homes were built in the Art Deco style. The term "drip" refers to a drip edge for moisture to “drip” off of stucco fascia edges, thus preventing it from running back across a soffit.

Manager's house in Lallaby Road, Drip Village

EZ was part of the Collins House group, an alliance of Anglo-Australian lead-zinc interests that had largely been based in Broken Hill that were linked through materials, capital and interlocking directorships. Along with the Broken Hill Proprietary Company (BHP) this group dominated heavy manufacturing development in the inter war period and introduced many new management practices into Australia. A number of these were first put in place at the Port Pirie lead smelters.

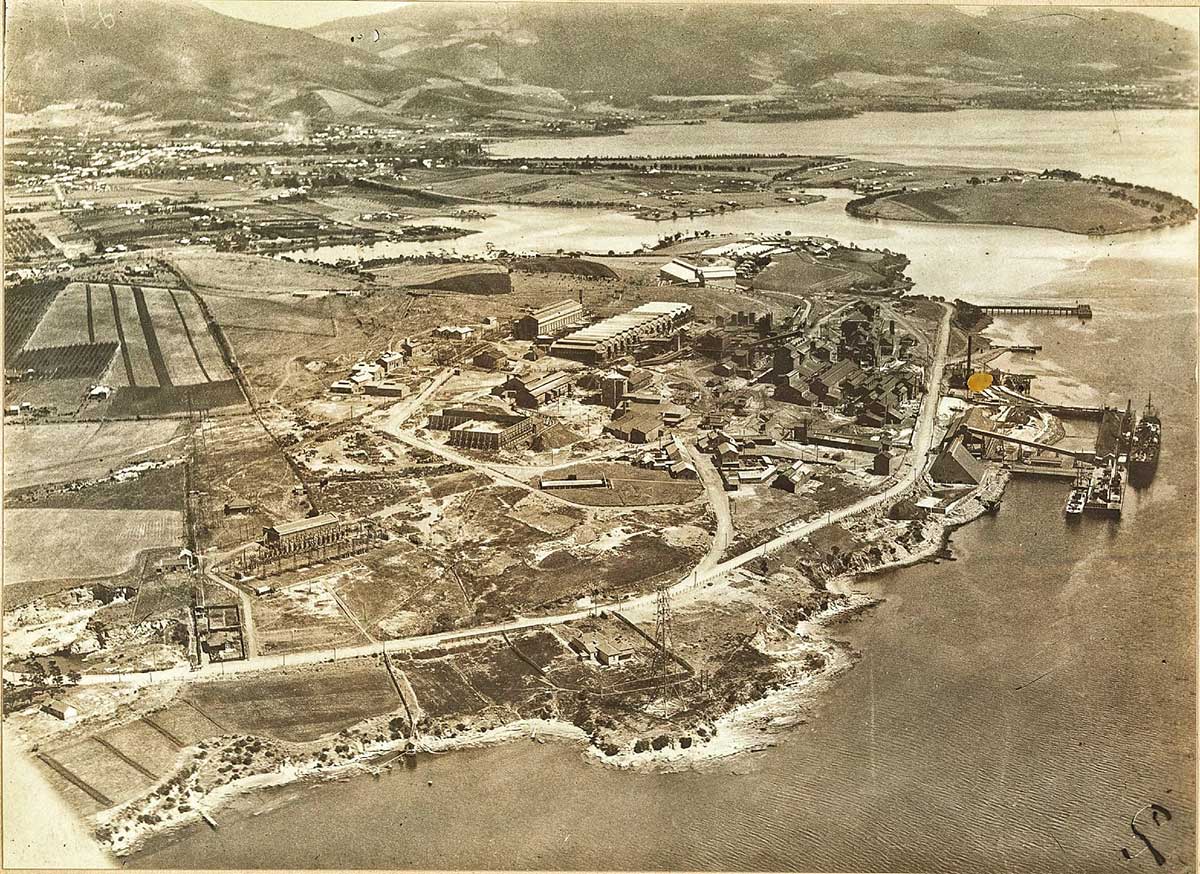

The establishment of EZ at Risdon was brought about by a number of factors, namely the decline of Britain as an economic force, government encouragement of manufacturing industries and the favourable orientation of most federal governments towards tariffs that favoured manufacturing interests. With a suitable political and economic climate, the availability of a vast amount of tailings from Broken Hill, and the development of the new electrolytic smelting process meant that the material and technology was available to enable the Collins House group to produce zinc economically. Tasmania’s cheap hydro electricity provided the incentive to establish the factory at Risdon in Hobart.

Herbert Gepp, EZ’s first General Manager, initially worked as an engineer with the Zinc Corporation in Broken Hill. Like many of the Collins House directors and senior technocrats such as W.S. Robinson and Gerald Mussen, Gepp was influenced by the New Liberalism with its concerns about efficiency, labour productivity and cooperation. New Liberalism argued that for Australia to become a self-contained independent nation it required national efficiency, the maintenance of an ethical as opposed to a materialistic attitude of mind and the development of the spirit of industrial citizenship.

The initial construction and operation of the factory would require in excess of 1,000 workers and there were concerns that the poor condition, scarcity and costliness of rental and owner/buyer housing in Hobart would make it difficult for EZ to attract a workforce, leadimg EZ to adapt a policy of industrial welfarism in which the company would create both the workplace and the surrounding community.

Being a proponent of New Liberalism Gepps extablished a broad industrial welfare programme for EZ that centred on housing and cooperative activities, and included building a village to house the workers, would bring the workforce intimately close to the Works. The scheme would also place the workforce close at hand to deal with emergencies or any other unexpected needs.

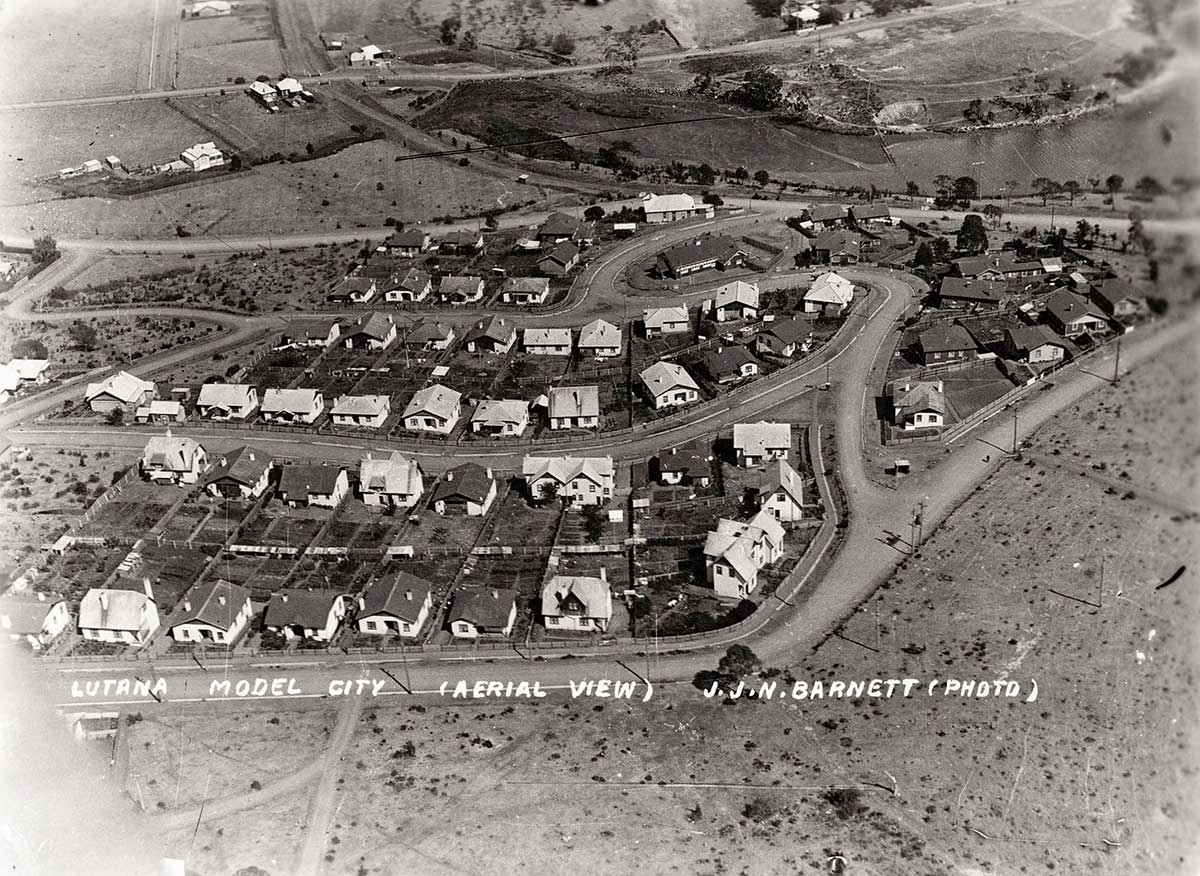

Lutana represented a bold attempt at a Garden City and drew its design inspiration from Ebenezer Howard’s concept of small community based garden cities with public ownership of land. This had its antecedents in the ideas of the English utopian socialists such as Edward Bellamy and William Morris.

The company bought eleven and a half acres at Risdon, known as Large’s estate, as the site of the Lutana village. Further land, which became known as the Orpwood estate, was purchased in 1919 on the high side of Bowen Road, just above Large’s estate. EZ initially proposed to build about 60 houses on Large’s estate for the accommodation of its employees and leave Orpwood’s estate undeveloped in the short term. In 1919 the eminent Melbourne architect Walter Butler was hired to facilitate the planning of the village.

134 and 136 Bowen Road, Lutana. EZ’s garden village houses

On the basis of Butler’s report, Gepp recommended to Collins House that 200 houses be constructed. The houses could be either rented or purchased, with care being taken to ensure that the lower paid men were allotted a large share of the houses. The Collins House directors proved to be less enthuiastic than Gebb. Whilst he took an approach that stressed the benefits of housing for the whole Works, the directors took a narrower view. Their concerns over the cost of the scheme resulted in the degradation of the original model garden village concept both in terms of scale and design.

Only eighteen artistically designed homes' had been completed by 1920, but unfortunately EZ’s garden village at Lutana was largely rejected by its workforce. The village was seen as remote from Hobart, the housing expensive, the concrete houses were viewed with suspicion and EZ’s subsidised railway tickets enabled people to live some distance from the Works.

EZ’s garden village houses

The village, numbering some sixty houses, was effectively complete by mid-1921, followed by a community hall in 1923.

Located on the hillside above the Brooker Inn, this quaint enclave of Arts and Crafts stucco rendered concrete, weatherboard and brick houses are today some of the most distinctive and significant buildings in Tasmania, and are rare examples of early twentieth century English-style company housing in this country.

EZ’s industrial welfare schemes also had uneven outcomes. Reforming and engaging with the workforce outside the factory gates eventually proved to be more difficult than Gepp and the Collins House directors anticipated.

The Full Story

"60 poured-concrete cottages, built in the Arts & Crafts style, have been constructed in Cook Street, Furneaux Ave, Cox Ave and Bowen Road, and tenants have moved in, as evidenced by the many established vegetable gardens. The village is an example of `benevolent capitalism'- a company providing quality housing for its workforce (Bourneville Estate at Claremont is another example)."

Info about the village's history from Dr Alison Alexander's book `A Heritage of Welfare & Caring: The EZ Community Council'. Photographer: JJN Barnett, probably taken sometime in the 1930s.

The zinc works at Lutana, is the largest exporter in Tasmania, generating 2.5% of the state's GDP. It produces over 250,000 tons of zinc per year. The refinery was often given other names such as the Risdon works, its operations are tied in with the mining of zinc in Rosebery on the West Coast of Tasmania. Zinc is used in galvanising, diecasting and pharmaceutical products and Zinifex’s output is bought by manufacturing, chemical and engineering companies in Asia.

Pollution from the works was an issue for the company, and successor companies that operated the works as well as disposal of waste out to sea. Electrolytic Zinc or the Electrolyic Zinc Company of Australasia operated the zinc refinery on the banks of the Derwent River between 1916 and 1984. Its current operator is Nyrstar N.V., a Belgium-based, global multi-metals business, with a market leading position in zinc and lead and growing positions in other base and precious metals, such as copper, gold and silver.