Like the Tasmanian Tiger, there are no emus in Tasmania any more as it is now extinct. The Tasmania Emu, after which the river and the bay on which Burnie stands were named, is believed to have been a smaller sub-species of the mainland emu. The external characters used to distinguish it were its whitish instead of a black foreneck and throat and an unfeathered neck.

The Tasmanian Indigenous people’s sustainable relationship with the emu also suggests emu population numbers were significant. The Tasmanian emu was regularly symbolised in Indigenous art, in their ceremonies it was common practice for Tasmanian Aborigines to dance and characterise emus by stretching out one arm to emulate the long neck of the bird. Feathers were used to decorate inside Aboriginal huts, and served as insulation and floor coverings.

The indigenous people used a substance called ‘patener’, made from a ground metal mixed with emu fat/oil, to mark their heads and bodies. Emus featured in stories and songs, and there were many different names for them, including gonanner, ponanner and tooteyer. There are many references to the emu in early colonial records too, with many place names recalling it, eg. Emu Hill, Emu Heights, Emu Point.

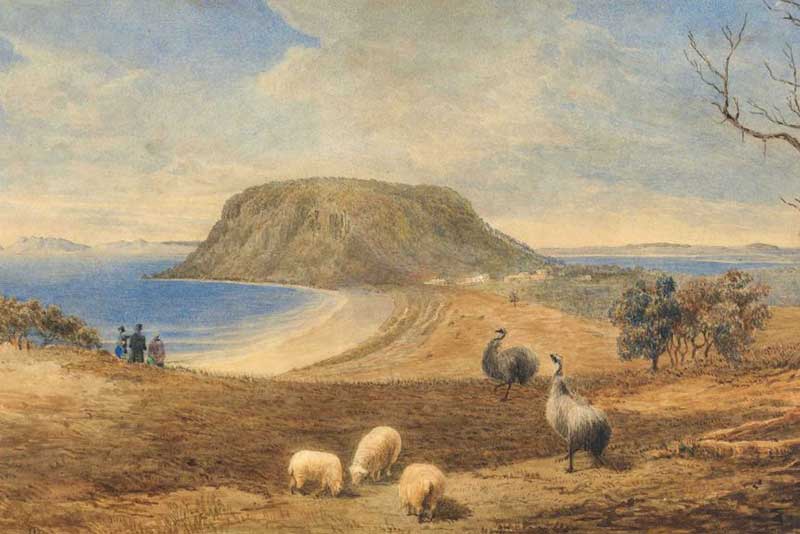

A watercolour by William Porden Kay depicts emus at Stanley during the 1840s. (Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, State Library of Tasmania)

Like the Tasmanian Aborigines with whom it had co-existed for thousands of years, the Tasmanian emu suffered a calamiltous fate with the arrival of white man. By the time of Henry Hellyer's encounter with emus at Emu Bay in 1827 when he named the bay after them because of their significant numbers, southern Tasmania's emu population was already in decline and within 40 years the species would be extinct. Though Emu Bay was once a stronghold for these flightless birds, their populations also diminished quickly after white settlers moved in. When the Burnie settlement was surveyed in 1846, the Tasmanian Emu was almost gone. The species survived in the wild until 1865, and the last captive bird died in 1873.

During those years, land was being cleared at an astronomical rate. The emu's habitat was quickly destroyed to make way for grazing land for sheep. By 1840, there were 280,000 sheep in Tasmania.

The introduction of dogs is also considered a major contributing factor to the fast extinction of the Tasmanian emu. Though it was a really important food source for the Aboriginal people who hunted emus, it was in relatively low numbers. Emus were pretty hard to catch, they were fast runners and could defend themselves. That all changed with the introduction of the domestic dog. Prior to the arrival of Europeans, Van Diemen’s Land did not have a domestic dog, nor was the dingo present. But the Europeans had dogs and guns and that combination proved deadly for the emu and hastened its extinction.

The island of Tasmania was home to the Thylacine, a marsupial equivalent of a wild dog (dingo). Known colloquially as the Tasmanian Tiger because of the distinctive striping across its back, it became extinct on mainland Australia much earlier because of the introduction of the dingo.

Due to persecution by farmers, government-funded bounty hunters, and, in the final years, collectors for overseas museums, it also appears to have been exterminated in Tasmania. The last known animal died in captivity in 1936. Many alleged sightings have been recorded, none of them confirmed.

More

The Lake Pedder earthworm (Hypolimnus pedderensis) is an extinct earthworm species in the family Megascolecidae. Its genus Hypolimnus is monotypic. It was endemic to the Lake Pedder area in Tasmania, Australia, prior to its flooding in 1972 for a hydro-electric power scheme.

It is only known from a specimen collected from a Lake Pedder beach in 1971. A 1996 survey failed to find it and it is presumed extinct.

An unuual-looking fish with bulging eyes, a mohawk-like fin on its head and the ability to walk on the seafloor with its pectoral and pelvic fins has reached a grim milestone. The so-called smooth handfish (Sympterichthys unipennis) has been declared extinct, the first modern marine fish on record to completely vanish, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

200 years ago, the smooth handfish was so plentiful in Australia — where it basked in Tasmania's warm, coastal waters — that it was among the first fish species to be scientifically documented Down Under. In 1802, French naturalist François Péron nabbed the first specimen of the odd-looking creature with a dip net in southeastern Tasmania, a feat that worked because handfish live in shallow waterss.

Now, Péron's specimen is the only smooth handfish scientists have left to study. It's not that researchers haven't been looking. Despite extensive underwater surveys along the Australian coastline, the smooth handfish hasn't been sighted for many years, meaning that Péron was the only scientist on record to collect one, according to a 2017 study in the journal Biological Conservation.

The fishing activities that probably contributed to the extinction of the smooth handfish ended 53 years ago. The scientists note in their Redlist assessment that "this species was probably impacted, through both direct mortality as bycatch and destruction of habitat, by the large historical scallop fishery that was active in the region through the 20th century until the fishery collapsed in 1967". So, we didn't hunt or overfish the handfish to extinction—it wasn't being targeted. We overfished the scallops and the handfish was caught in the crossfire.